2013 AIA Top Honor Award- Acido Dorado and Rosa Muerta

Video shot by Nathalie Canguilhem and Anthony Vaccarello with Travis Scott, Vittoria Ceretti, Steffy Argelich

Here is the text –

Robert Stone isn’t here to play the nostalgia game.

He grew up in Palm Springs, yes, but not in the Rat Pack fantasy version that shows up on souvenir coasters. His dad built houses throughout the Coachella Valley: clean-lined, sun-bleached, quintessential desert. The family lived in a revolving door of them, often packing up and moving on as soon as the next one was ready.

“I basically do the architecture version of what he did,” Stone says now with a shrug.

Stone has the look of someone who’s spent years in the desert, and even longer thinking about why things are the way they are. Clean-shaven, lean, tall, he carries himself with a kind of alert intensity, like he’s listening to something other people can’t quite hear. There’s no performance in the way he talks, just a deep, practiced habit of paying attention. It’s easy to imagine him building a house the same way he builds a thought: piece by piece, until it holds.

His fluency in the visual vocabulary of the desert — the breeze blocks, the long shadows, the just-so landscaping — means he can stretch it, twist it, question it, and ultimately interpret it into something thornier. Something truer. Beyond that, Stone’s work is far more slippery to define: intimate but not sentimental, architectural but also theatrical, deeply Californian but never obedient to the party line.

His latest project, a recently completed estate in Rancho Mirage, offers the clearest expression yet of that evolving vision. Set on a sweeping 3.83-acre lot that used to be a date field, the house is surrounded by panoramic mountain views and anchored by Stone’s ambition to define a new desert architecture. Blending elements of classic modernism with Spanish influences, the home isn’t easily labeled, and that’s the point. It’s a residence that asks to be experienced rather than explained, grounded in its environment while challenging the conventions of what desert living is supposed to look like.

“In general, I look at things and try to see them for what they are and disconnect them from past ideas to understand what they mean now,” he says.

In the context of Palm Springs design, that’s borderline heresy. But Stone doesn’t mind being the guy who mutters something unsettling at the cocktail party.

“People here love architecture. I should say they love dead architects,” he says with a dry laugh. “There’s this excitement around modernism that is great, but most think modern equals new — it’s 80 years old. I mean, it’s really old.”

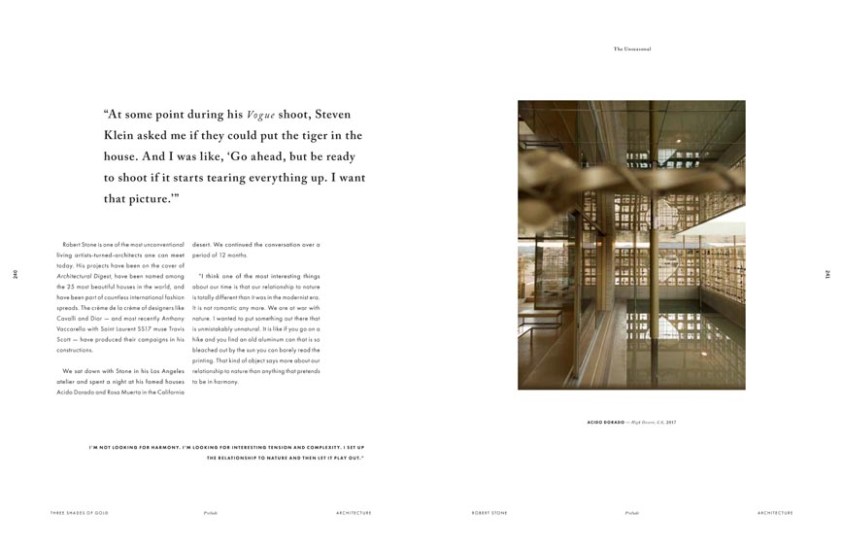

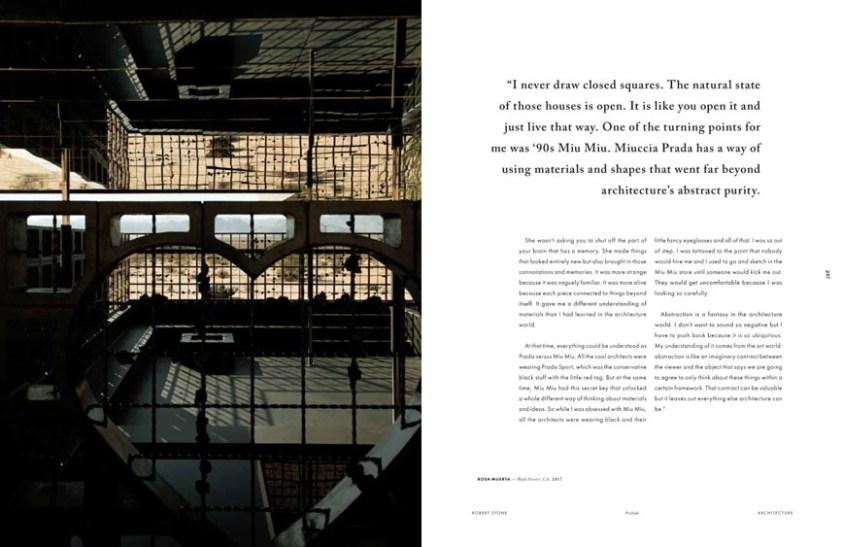

This ambivalence is what gives Stone’s buildings their edge. His earlier homes in Joshua Tree — Acido Dorado, all gold and mirrors and theatrical stillness, and Rosa Muerta, black as an oil slick and just as provocative — weren’t designed to stay in their lanes. They were meant to unsettle, shimmer, seduce. And that’s exactly what they’ve done.

Acido Dorado was featured in Vogue Italia, shot by Steven Klein for Roberto Cavalli in a lavish, high-gloss campaign that matched the house’s surreal energy. Rosa Muerta, meanwhile, has appeared in Elle Décor, Dwell, and even Playboy, and has served as a location for underground fashion labels and avant-garde video shoots. Over the years, both houses have developed cult status — worshipped by architecture nerds, rented by stylists, and sometimes mistaken for conceptual art installations. Which, honestly, they are.

Then there’s the “punk rock architect” moniker, a label Stone doesn’t exactly reject, though he’s quick to clarify the spirit behind it.

“A lot of my worldview comes from being a nerdy punk. I would read Maximum Rocknroll magazine from cover to cover, and I believed in punk as an intellectual exercise,” he says.

For him, punk isn’t about destruction. It’s about initiative. Imagination. The willingness to create something better, not just stand around sneering at the status quo: “So I talk the punk guy, but the intention is to inspire.”

It’s fair to say Stone isn’t designing rebellion for rebellion’s sake. He’s trying to crack things open, let in a little air. This perspective informs his own work as an architect and designer, which both engages with and subverts the legacy of modernism.

“Post-modernism in architecture was misconstrued with irony. I’m interested in post-modernism without the irony,” he adds. “Sincerity is the only thing that changes people’s minds or inspires them.”

It’s a clarifying ethos: DIY but make it architecture. His buildings don’t just buck trends, they interrogate them. Why do we live the way we do? Who decided that glass boxes were aspirational? Why does the desert feel like an Instagram loop of itself? How can we design the future?

What Informs His Work-

Stone came of age as an architect in the 1990s, just as modernism was entering its glossy commercial renaissance. “In the ’90s, all of a sudden, the design culture kind of came up around Apple computers and that whole consumer tech aesthetic. People wanted modern houses that looked like that, and architects who were my professors were like, ‘Wow, we can actually make money doing this!’ — which meant that we were going to be doing this for a few decades.”

For Stone, the alignment between advertising, product design, and architecture was a warning sign. “I was sure that when we opened architecture magazines and all the product ads were the same as the featured houses in it, it was all locked in, and no new ideas were allowed.”

It was a realization that both repelled and galvanized him. Rather than chase the slick, commodified version of modernism that was becoming the norm, Stone turned toward something more personal. He wanted to make work that felt less like branding and more like art. Something that resisted consumption and invited contemplation.

“I was trying to find a way to make something that felt more like poetry,” he says. “I ended up gravitating toward the aesthetic language that I understood the best.”

That language, inevitably, was the desert. “I felt like I had a familiarity with this place and the aesthetics,” he continues.

Joshua Tree, where his earlier projects landed, gave him the space to explore that mystery. The rawness of the landscape amplified his designs, making them feel like ruins from the future or sets from some forgotten dream.

“It benefits from the raw landscape around it,” he says. “So I can do something up there with this kind of weird memory of modernism, and it’s made more powerful by the raw desert around the house. Whereas down here, the context is different.”

His homes don’t behave the way desert homes are supposed to. They confront the terrain. Engage it. Poke at it. They shimmer, shift, unsettle — sometimes beautiful, sometimes strange, always provocative. They don’t ask to be liked. They ask to be felt.

“I do think I’ve found a way to make things here that feel like poetry,” Stone says again, doubling down on the sentiment. “Things that remind me of what I grew up around but also push against it. This is where I can make my best work.”

Underpinning it all is a clear critique of design culture’s current safe mode, all beige restraint and Instagram consensus. Stone sees that safety as cynicism. And for someone often labeled a provocateur, his motivation is surprisingly earnest.

“You don’t do this work if you’re not optimistic. The people who helped me put together this project, they are optimistic people, because they realized we can do something new here,” he says. “I think making the same sort of beige and gray ‘tasteful modernism’ that everybody knows how to value, that’s actually cynical.”

The Rancho Mirage Vision-

Growing up in Palm Springs gave Robert Stone a studied vantage point. He remembers the light, the heat, the geometry of the place, but also the strange choreography of fantasy and reality. “Palm Springs was always presented as this glamorous escape, but the reality was more complex. There was a whole infrastructure that supported that fantasy, and not everyone got to participate in the dream. That’s something I think about a lot in my work — who gets to define what’s beautiful, and why?” That tension between the image and the infrastructure, the spectacle and the scaffolding runs through everything Stone builds. It’s what led him to develop a style that’s both cerebral and tactile, rooted in the desert but never beholden to it. “Perfection is boring,” he says. “The things that stay with you, that feel alive, are always the ones that have some kind of tension.” His Rancho Mirage project — a pair of structures called Dreamer and Lil’ Dreamer, their names a nod to West Coast street culture — exemplifies that philosophy and then some.

The brutalist concrete walls feel immovable, almost ancient, but they’re softened by flashes of metallic surfaces that shift with the sun. These are buildings that play with scale and drama: diagonal rooftop planes, voids and shadows, punctuated by unexpected moments of intimacy. It’s not modernism, and it’s not a total rejection of it either. It’s a conversation — between then and now, between fantasy and materiality.

“I wanted to create something that wasn’t easy to digest,” Stone says. “A place that makes you stop and think.”

Unlike the pristine white boxes that populate many desert developments, his house revels in texture and materiality. The composed breeze blocks are sculptural and expressive, each intentionally placed. Even the landscaping resists easy categorization. Stone embraced artificial turf, extending the aesthetic into the interior with a green carpet.

Nowhere is his ethos more visible than in the silver Spanish roofing tiles, a nod to traditional clay tile roofs but rendered in a way that feels almost alchemical.

“This metallic tile roof thing, I’ve been using that idea in my sketchbooks and my studio work for 30 years,” he explains. “The material is basically pottery, so I did some experiments using metallic glaze on it, and it transformed. It has a handmade texture, but the metallic finish and futuristic silver color bring opposites together. That and a totally new way to make a roof shape interact with the building — it’s like a Spanish space ship.”

Another element adds a layer of wit and critique to the structures. Perched on the rooflines are what appear to be air conditioning units, except they’re not functional. They’re sculptures — perfect metallic cubes with softened edges and smoothed louvers, finished in gleaming gold. Stone designed them as a kind of architectural jewelry — minimal yet flashy, familiar yet strange.

“The idea is to make something we all ignore into a decorative part of the house,” he says.

It’s more than a visual gag. The gold AC cube is part commentary, part homage. “There’s a whole history of the cube in minimalist sculpture from Larry Bell onward,” Stone says.

It’s also a meditation on how we experience the desert: how we pretend to live in communion with nature while hiding behind the hum of climate control. It’s a sly wink, one that calls into question the entire fantasy of desert living.

“The air conditioner is the thing that makes houses livable down here, and yet we ignore them,” he says. “We pretend we’re living in nature, but it’s air-conditioned nature. I think that’s more interesting.”

Stone spent years inhabiting the ideas for this Rancho Mirage project, his first on home turf. It wasn’t just another commission; it was a personal reckoning with the landscape that shaped him. He wanted to get it right. Every material, every slope, every glint of gold was a deliberate choice, because the point wasn’t to build something beautiful, it was to make something true.

Stone’s designs are places to live, sure, but they’re also places to wake up — to how we shape the spaces around us, to how those spaces, in turn, reflect what we value, what we believe, what we feel. If the desert has taught Stone anything, it’s that architecture doesn’t need to be nostalgic or new, minimal or maximal, it simply needs to say something.

Mert & Marcus shot Mariacarla Boscono, Heidi Klum, and Angela Lindval at Acido Dorado for Roberto Cavalli.

Photographer Mona Kuhn’s book “She Disappeared into Compete Silence” is 104 pages of art photography shot at Acido Dorado over a few summers. Available from Steidl books.

Mariano Vivianco shot Joan Smalls for Harpers Bazaar at Acido Dorado

Michele Laurita shot Celia Becker for Sorbet in Yves Saint Laurent 2017

Camilla Akrans fashion editorial for Harpers Bazaar with Karlina Caune

Melina Matsoukas project at Rosa Muerta with Beyonce and Jay Z

Three Shades of Gold.

We had a year-long dialogue with American artist-turned-architect and punk modernist Robert Stone about his unique approaches and perfect backdrops for the fashion world’s upper crust.

Words: Ger Ger & Julia Koerner / Images: Ger Ger

“At some point during his Vogue shoot, Steven Klein asked me if they could put the tiger in the house. And I was like, ‘Go ahead, but be ready to shoot if it starts tearing everything up. I want that picture.”‘

Robert Stone is one of the most unconventional living artists-turned-architects one can meet today. His projects have been on the cover of Architectural Digest, have been named among the 25 most beautiful houses in the world, and have been part of countless international fashion spreads. The creme de Ia creme of designers like Cavalli and Dior – and most recently Anthony Vaccarello with Saint Laurent SS17 muse Travis Scott – have produced their campaigns in his constructions. We sat down with Stone in his Los Angeles atelier and spent a night at his famed houses Acido Dorado and Rosa Muerta in the California desert. We continued the conversation over a period of 12 months.

“I think one of the most interesting things about our time is that our relationship to nature is totally different than it was in the modernist era. It is not romantic any more. We are at war with nature. I wanted to put something out there that is unmistakably unnatural. It is like if you go on a hike and you find an old aluminum can that is so bleached out by the sun you can barely read the printing- That kind of object says more about our relationship to nature than anything that pretends to be in harmony. I’m not looking for harmony. I’m looking for interesting tension and complexity. I admit that relationship to nature and then let it play out.”

“I was looking for a way to make architecture that felt more meaningful. I’m building houses, I’m not building airports, I’m not building museums. I think they can work just like a really nice song. They can be strange, they can be mysterious, and they can feel like they are yours alone.”

“I don’t design the perimeter for something and then put holes in it. I design intersections of planes and then figure out how to enclose it. It is a modernist approach, but one that I have tried to push much further. The natural state of the building is continuous with that abundant space all around it. The natural state of those houses is open”

“One of the turning points for me was ’90s Miu Miu. Miuccia Prada has a way of using materials and shapes that pointed far beyond architecture’s abstract purity. She wasn’t asking you to shut off the part of your brain that has a memory. She made things that looked entirely new but also brought in connotations and memories. It was more strange because it was vaguely familiar. It was more alive because each piece connected to things beyond itself. It gave me a different understanding of materials than I had learned in the architecture world.”

“At that time, everything could be understood as Prada versus Miu Miu. All the cool architects were wearing Prada Sport- which was the conservative black stuff with the little red tag. But at the same time, Miu Miu had this secret key that unlocked a whole different way of thinking about materials and ideas. So while I was obsessed with Miu Miu, all the architects were wearing black and their little fancy eyeglasses and all of that. I was so out of step. I was tattooed to the point that nobody would hire me and I used to go and sketch in the Miu Miu store until someone would kick me out. They would get uncomfortable because I was looking so carefully. “

“Abstraction is a false fantasy in the architecture world. I don’t want to sound so negative but I have to push back because it is so ubiquitous. My understanding of it comes from the art world: abstraction is like an imaginary contract between the viewer and the object that says we are going to agree to only think about these things as abstract shapes, forms and light. That contract can be valuable, but it isn’t real- It leaves out everything else architecture can be.”

“I have always been much more interested in fashion and photography than in empty architecture. I want the houses to be portrayed in the way bodies connect to them and the way people bring poetic ideas to them- not just as empty abstract sculptures. So it is almost natural that it is also a perfect stage for fashion. Architecture is only part of the equation. Movements of a tiger can complete it as much as the life anyone brings to it.”

“Growing up in Palm Springs felt more Larry Clark than Julius Shulman. It was about actually living in these modernist houses, using them and sometimes destroying them. “

“There is this strange historical overlay between skateboarding and the decline of modernism. In the ’80s, they didn’t put transitions in pools anymore: they built pools square and you can’t skate them. So we would search for pools by looking at the architecture. You would know from the street that a mid-century modernist house was going to have a rounded pool in the backyard. So, I was looking at modernism before I knew anything about architecture. I saw it lived in, used, and abandoned. I think it gave me a more complicated understanding of how the modernist project overlaid with real life. “

“I learned that you have to let in some negatives to make things more interesting. There has to be some awkwardness to re-define beauty for our time. So, not everything is positive in my work. It’s not just about “nice”. The two-way mirrors, for example, come from this idea of engaging in a dialogue with the corruption of late-modernism, the part where it got dark, corporate, like us, like our world. I mean, simplistic mid-century nostalgia is boring, but I love the end of the sixties where the ideals started to turn on us and got interesting.”

“If all my roofs cave in and my houses burn down, they still are going to look really good. I’m designing architecture that I want to look good in ruins.”

“Am i a dreamer?-All the time. It is like air for me, it is like the water for the fish.”

Here is the text –

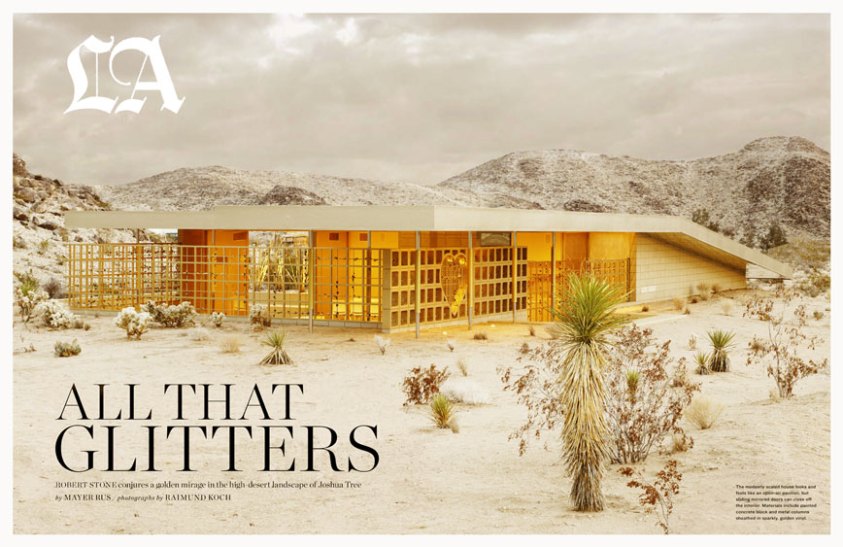

ALL THAT GLITTERS- Robert Stone conjures a golden mirage in the high-desert landscape of Joshua Tree

by Mayer Rus

Forget midcentury modern. Forget deconstructivism, expressionism and all the other convenient “isms” that have traditionally been applied to the discussion of architecture. Robert Stone is far more interested in the stories buildings tell, the personal and cultural iconography they manifest and, yes, even the feelings they evoke. “I’m proposing something a little more demanding than a new aesthetic. I’m not saying, ‘This shape is cool’ or ‘Stacked boxes are in, and slanty walls are out.’ I’m asking people to think about how architecture works and what makes it meaningful,” says the LA-based Stone.

Acido Dorado is a trippy place. With its gold-mirrored ceiling and walls, heart-shape concrete-block cutout and gilded cage of twisted metal rods strung with wrought-iron flowers, the house seems an alien-albeit strangely congruous-presence in the parched high-desert panorama of Joshua Tree. Think Guns N’ Roses and Lost in Space…or 2001: A Cocaine Odyssey…or Zeus visiting desert Danae in a shower of gold. Think golden showers.

In fact, think whatever comes to mind. Stone eschews fixed meanings and revels in multiple interpretations and gut reactions. “Architecture should support what people bring to it,” he insists. “My work asks viewers to look inward. I’m telling people that they already get it-they just need to be open to it.” Acido Dorado-“golden acid” in Spanish-is Stone’s second rental house in the Coachella Valley, a short distance from Rosa Muerta, his black-shrouded groovy-Gucci-goth fantasy. The architect gave these seriously alluring follies Spanish names both as an earnest nod to the pervasive Latino culture of Southern California and a tongue-in-cheek riff on the common practice among developers of using foreign names to ennoble their often shabby properties with a gloss of romance and mystery.

When pressed to describe the physical form of Acido Dorado and the materials he employed, Stone instead weaves a tapestry of personal inspirations: military hardware, burned-out houses, Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion, preppy, BMX, Versace fall 2009, Gordon Matta-Clark, Ed Ruscha, Hedi Slimane, lowriders, sandstorms, macrame, drugs, roadside death shrines, classic desert modernism, evil corporate modernism, Robert Smithson’s Mirror Displacements, Robert Morris’ brutal minimalism and empty pools.

“Everyone has their own obsessions. I admit mine and try to incorporate them into my architecture rather than dressing them up in abstract language,” Stone says.

While many architects disparage fashion as a frivolous discipline lacking the gravitas of the heroic builder, Stone celebrates couture without apology. “I think that capturing a moment in time and transforming it into something profound is the hardest thing to do. Fashion designers talk about their work as a personal response to the world around them. Down the road, we see some of the things they create as era-defining,” he avers. “Architecture is a person’s life-a lens that opens up new possibilities. And yet architects aren’t trained to trust their gut.”

If Stone sounds skeptical about traditional architectural education and discourse, it’s because he is. Rather than taking the established path of internship and enslavement in a professional office, followed by the opening of an independent practice and the requisite hat-in-hand courting of clients to build a portfolio, he decided simply to go to the desert and make architecture-with his own two hands. “I appreciate the directness of building by hand,” he says, “whether it be digging ditches or fashioning metal roses. The DIY thing raises the stakes. If I’m going to take three years and put in my own money, then I have to ask myself, What is it going to be?’

This, of course, begs the question, Exactly what is it? Manifesto? Pleasure dome? Provocation? Stone believes it’s all of these things, plus whatever anybody else decides to bring to the glossy, mirror-topped table.

Cover of the 25 most beautiful houses in the world issue!

Copyright © 2010-2025 Robert Stone Design