Here is the text –

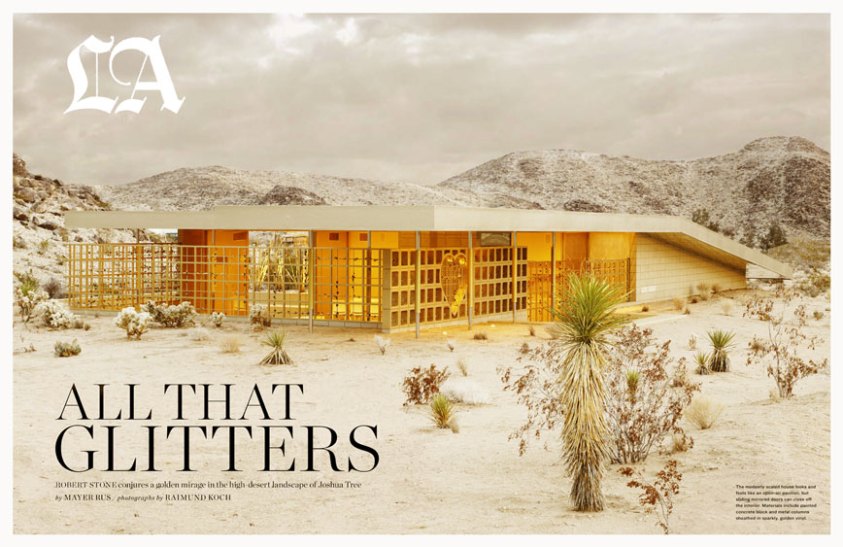

ALL THAT GLITTERS- Robert Stone conjures a golden mirage in the high-desert landscape of Joshua Tree

by Mayer Rus

Forget midcentury modern. Forget deconstructivism, expressionism and all the other convenient “isms” that have traditionally been applied to the discussion of architecture. Robert Stone is far more interested in the stories buildings tell, the personal and cultural iconography they manifest and, yes, even the feelings they evoke. “I’m proposing something a little more demanding than a new aesthetic. I’m not saying, ‘This shape is cool’ or ‘Stacked boxes are in, and slanty walls are out.’ I’m asking people to think about how architecture works and what makes it meaningful,” says the LA-based Stone.

Acido Dorado is a trippy place. With its gold-mirrored ceiling and walls, heart-shape concrete-block cutout and gilded cage of twisted metal rods strung with wrought-iron flowers, the house seems an alien-albeit strangely congruous-presence in the parched high-desert panorama of Joshua Tree. Think Guns N’ Roses and Lost in Space…or 2001: A Cocaine Odyssey…or Zeus visiting desert Danae in a shower of gold. Think golden showers.

In fact, think whatever comes to mind. Stone eschews fixed meanings and revels in multiple interpretations and gut reactions. “Architecture should support what people bring to it,” he insists. “My work asks viewers to look inward. I’m telling people that they already get it-they just need to be open to it.” Acido Dorado-“golden acid” in Spanish-is Stone’s second rental house in the Coachella Valley, a short distance from Rosa Muerta, his black-shrouded groovy-Gucci-goth fantasy. The architect gave these seriously alluring follies Spanish names both as an earnest nod to the pervasive Latino culture of Southern California and a tongue-in-cheek riff on the common practice among developers of using foreign names to ennoble their often shabby properties with a gloss of romance and mystery.

When pressed to describe the physical form of Acido Dorado and the materials he employed, Stone instead weaves a tapestry of personal inspirations: military hardware, burned-out houses, Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion, preppy, BMX, Versace fall 2009, Gordon Matta-Clark, Ed Ruscha, Hedi Slimane, lowriders, sandstorms, macrame, drugs, roadside death shrines, classic desert modernism, evil corporate modernism, Robert Smithson’s Mirror Displacements, Robert Morris’ brutal minimalism and empty pools.

“Everyone has their own obsessions. I admit mine and try to incorporate them into my architecture rather than dressing them up in abstract language,” Stone says.

While many architects disparage fashion as a frivolous discipline lacking the gravitas of the heroic builder, Stone celebrates couture without apology. “I think that capturing a moment in time and transforming it into something profound is the hardest thing to do. Fashion designers talk about their work as a personal response to the world around them. Down the road, we see some of the things they create as era-defining,” he avers. “Architecture is a person’s life-a lens that opens up new possibilities. And yet architects aren’t trained to trust their gut.”

If Stone sounds skeptical about traditional architectural education and discourse, it’s because he is. Rather than taking the established path of internship and enslavement in a professional office, followed by the opening of an independent practice and the requisite hat-in-hand courting of clients to build a portfolio, he decided simply to go to the desert and make architecture-with his own two hands. “I appreciate the directness of building by hand,” he says, “whether it be digging ditches or fashioning metal roses. The DIY thing raises the stakes. If I’m going to take three years and put in my own money, then I have to ask myself, What is it going to be?’

This, of course, begs the question, Exactly what is it? Manifesto? Pleasure dome? Provocation? Stone believes it’s all of these things, plus whatever anybody else decides to bring to the glossy, mirror-topped table.